Dear Kaylen,

I use my paws for all kinds of things. That’s how I adjust my microscope, set up my microphone for a podcast and write answers to science questions. But most cats don’t do those things. Maybe that’s why cats don’t have fingerprints like yours.

I asked my friend Katherine Corn about that. She’s an evolutionary functional morphologist. She studies how animal bodies evolved to do all kinds of jobs. She’s the director of Washington State University’s museum of vertebrate zoology.

The Charles R. Conner museum is like a library. But instead of books, it has more than 65,000 vertebrate specimens like birds, fish and mammals. Some of those are on display for anybody to come see. Some are put away for researchers. Studying specimens in museums helps scientists answer important questions. ©WSU

Scientists think there are two big reasons for fingerprints: dexterity and grip.

“We can’t really discriminate which one is more important,” Corn said. “But people are working on this, which is exciting.”

Dexterity is the way you use muscles in your hands to make small, precise movements. That’s how you write, type or use a game controller. It’s also called fine motor control.

To make those exact movements, you take in data and make little adjustments. That data comes from what you see and hear. It comes from what you feel and how you sense your body in space.

If you’re gaming, you adjust your hand movements based on things you see and hear in the game and in the real world. You feel the controller. You can tell how your fingers and hands are moving. Your brain uses all that information to tune your movements.

Your sense of touch works because your skin has tiny touch sensors. They’re called Meissner’s corpuscles. They help you feel different textures. Primates like monkeys and apes have lots of these. Humans are among the apes with the most.

“Humans—Homo sapiens—have like a zillion of these mechanoreceptors,” Corn said. “And our mechanoreceptors are really big.”

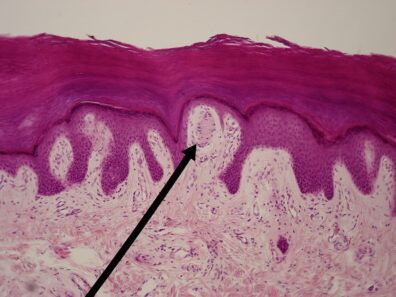

Here’s what a Meissner’s corpuscle looks like under your skin. They’re sensitive to touch and vibrations. Wbensmith CC BY 3.0

Scientists think the ridges of your fingerprints act like little levers. As you touch something, those ridges push on touch sensors. That gives your brain lots of information about what you touched.

It’s possible that this dexterity evolved as primates began eating more fruit. Being able to feel subtle textures would have helped them figure out if fruit was ripe.

Grip is how you hang onto things. To do that well, your fingers need to be moist but not sloppy. If your skin is too dry, it won’t flex right. If it’s too wet, you’ll lose friction and slip off.

The ridges of your fingerprints are like tiny furrows or channels that move moisture. Those ridges spread your sweat around, so your skin is flexible but not too slippery.

Fingerprints also help grip rough surfaces because the ridges lock in with the bumps and grooves on the surface. Some animals do this super well. It’s how geckoes cling to smooth surfaces like glass with their mega-ridged feet.

This is close-up of a gecko’s foot. The extreme ridges on their toes help them cling to smooth surfaces. Bjørn Christian Tørrissen CC BY-SA 3.0

“We can’t crawl up a window,” Corn said. “But the same principle applies that we create little friction sets on a rough surface.”

Animals usually don’t evolve traits that do just one thing. Fingerprints helped early humans succeed in a few ways, so those fingerprints stuck around.

That’s why human fetuses form fingerprints way before they’re born. The unique pattern of ridges happens because of genes, the density of the fluid inside the uterus and how the fetus moves around while the ridges form.

It’s a clever adaptation that gives humans a hand up on the competition.

Sincerely,

Dr. Universe