Dear Colleen,

When I was little, I liked to move the radio dial in the car. I could hear different channels with music or talking. Plus, static in between.

My friend Ben Belzer reminded me of that when we talked about your question. He’s an engineer at Washington State University.

“Your cell phone is basically a digital radio,” Belzer said.

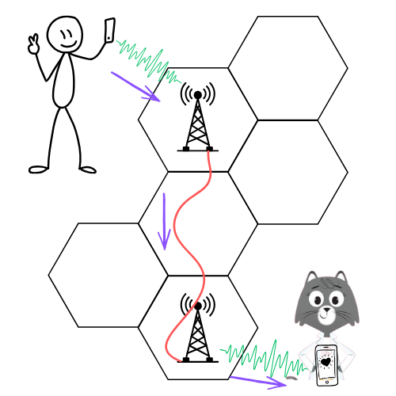

Any place with cell phone coverage gets divided into cells. They could be six-sided hexagons like the cells in a beehive. Or they could be any shape with flat sides. The size of the cell depends on how many people live there. A cell tower stands in the middle of each cell.

Every cell contains a cell tower. Messages travel through the air to the cell tower. They often move down cables between towers.

Let’s say you want to text to me in Washington. You type “hi” into your phone.

The computer in your phone translates “hi” into binary code. That’s computer language. It’s made of a string of 0s and 1s.

The letter h is 01101000 in binary code. The letter i is 01101001. So, “hi” looks like this: 01101000 01101001.

Your phone sends out invisible energy called radio waves. A transmitter inside your phone uses those waves to send me your message. It changes the radio waves—like how tall or fast the wave is—to represent the 0s and 1s in your message. That’s called modulating.

Your phone beams the modulated radio waves from your phone. They zoom through the air to the nearest cell tower. An antenna there catches the waves. Then, the cell tower sends the message all the way to the cell tower closest to me. Usually, it sends it through cables buried underground. Once it arrives at my nearest cell tower, that tower beams the radio waves to my phone.

A chip in my phone decodes the radio waves back into 0s and 1s. Then a processor in my phone converts those digits back into letters I can understand. It shows up as “hi” on my screen.

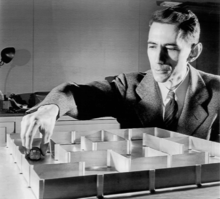

Claude Shannon figured out how to send information through binary code—like our phones do. Here, he’s working with a robot “mouse” he invented with researcher Betty Shannon. It was one of the first-ever experiments with artificial intelligence. Image: Bell Labs

Something similar happens if you send me a picture or voice call me.

For a picture, your phone’s computer breaks the image into dots called pixels. Then it maps the color and position of each dot using binary code. It’s kind of like how you graph information in math class—but with way more information than we can handle.

For a voice call, the microphone inside your phone picks up the vibrations of your voice. Those vibrations move a tiny magnet and coil to make electricity. Then your phone’s chip translates that electrical signal into binary code.

From there, your picture or voice travels from your phone to mine just like the text message did. All that happens incredibly fast. It’s so quick that we don’t even hear a delay when we chat on the phone.

When it comes to communication, cell phones really tower above the rest.

Sincerely,

Dr. Universe