Dear Maya,

I mostly keep all four paws on the ground. It’s hard to imagine living out in space.

I asked my friend Erica Crespi about it. She’s a biologist at Washington State University. She studies how animals tolerate stressors faced in the environment—including how humans can live and thrive in space.

Crespi told me that Valeri Vladimirovich Polyakov lived on the Mir Space Station for 437 days and 18 hours in the 1990s. So far, that’s the record for living in space.

Polyakov’s job was to test the effects of a long space flight—like maybe a trip to Mars. He handled the stress super well. The hardest parts were the first few weeks in space and back on Earth.

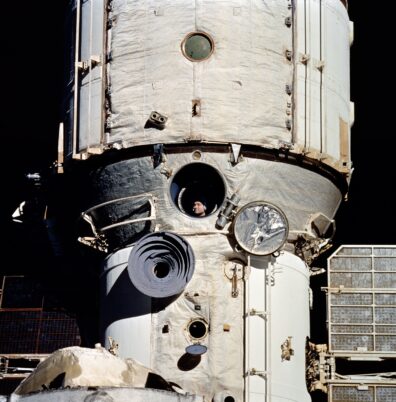

Here’s Russian cosmonaut Polyakov peeking out of the Mir core module in 1995. The module was meeting up with NASA’s space shuttle Discovery. Polyakov had been in space for over a year at this point.

But living away from Earth is no easy mission.

“Our species evolved for life on Earth,” Crespi said. “The stressors there are different from what we grow up with here.”

On Earth, gravity pulls us toward the center of the planet. It’s why our feet stay on the ground. It’s why our muscles and bones are strong. When we walk or run, we work against the tug of gravity.

There’s almost no gravity in space. Astronauts float. That sounds fun, but without gravity, muscles shrink and bones weaken. Astronauts exercise about two hours every day to make up for it.

Low gravity even affects what’s going on inside the body. An astronaut’s heart works hard to move their blood around like usual. Some astronauts say that causes sinus pressure—kind of like having a cold all the time.

Crespi told me her research group wants to know how space affects the microbes inside astronauts. Those microbes help us digest food, make vitamins and fight off sickness. Low gravity and other stressors in space may make things harder for them, too.

Another problem is radiation. That’s energy from the sun and other places inside and outside our solar system. Too much radiation can make us sick or cause serious health problems. Earth’s atmosphere protects us from that. Spacecraft must be carefully built to shield astronauts.

Astronauts also don’t have trees or oceans to recycle air and water. They rely on machines to do those jobs, and to deal with space dust and extreme temperature.

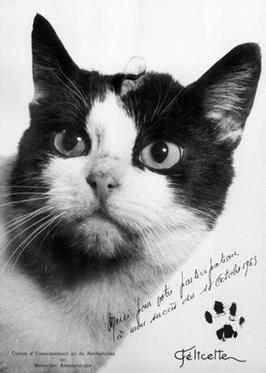

I haven’t been to space, but one other cat has. Her name was Félicette. France sent her into orbit in 1963. She spent 13 minutes among the stars.

Then there are the emotional challenges. Astronauts live in small, enclosed spaces. They can’t step outside to feel the breeze. They don’t have the familiar sights, sounds or smells of home. They miss their families and friends.

Even the sleep schedule in space is tricky. The space station orbits the Earth quickly. Outside its windows, the sun rises and sets every 45 minutes. Astronauts use lights and curtains to mimic the light-and-dark schedule on Earth.

But Crespi is optimistic that we’ll figure out how to keep humans happy and healthy in space. Right now, scientists are developing sensors to monitor astronaut health. They’re figuring out how to grow plants in space and recycle water more efficiently.

If we could farm in space, astronauts would have fresh, familiar foods. Those plants could recycle air and water. Plus, it feels good to be around plants.

Once more people—and maybe even cats—can stay in space longer, it would be less lonely for everyone. Maybe it would feel like visiting a little town in a space station.

That would help keep humans grounded while they reach for the stars.

Sincerely,

Dr. Universe