Dear Ines,

I have gray fur. But sometimes I think it’s getting grayer—like my human friends’ hair does as they get older.

I asked my friend Jiyue Zhu about that. He’s a biochemist at Washington State University.

He told me it’s a mystery.

“We still don’t completely comprehend this,” Zhu said. “It’s an active area of research.”

Aging seems to be related to the way cells duplicate.

DNA is a set of instructions for making your body. You keep a copy of your DNA folded up inside each of your cells.

All those cells have different life spans. Some, like your skin cells, get replaced often. Some, like your heart cells, last your whole life or only duplicate rarely.

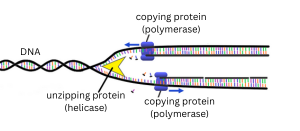

Your cells copy their DNA every time they duplicate. One protein unzips your DNA. Another protein zooms along it, building a copy of the DNA.

DNAs are double-stranded molecules. This is what it looks like when the two strands of DNA unzip and gets copied. Each daughter DNA has one old strand and one new strand. Image: Christinelmiller CC BY-SA 4.0, simplified by Dr. Universe

Usually that works well. But it’s not perfect. Sometimes errors happen during duplication.

“Over time, errors accumulate,” Zhu said. “Even with a very low error rate, if you duplicate cells millions or billions of times, those errors build up.”

Most of the time, your body sees those errors and fixes them. But some fall through the cracks.

When enough mistakes or other damage build up, the cell may trigger senescence. That’s like retirement for a cell. It stops doing its job. It stops duplicating.

But it can cause problems—like sending out signals that harm healthy cells or making your immune system work hard to clear those retired cells out. Older people have more retired cells than younger people do.

The second thing we know about aging is that the ends of your DNA take on a specific kind of damage. They’re like the plastic bits at the ends of your shoelaces. Without those caps, the shoelaces fray and become less useful.

The end caps on your DNA are called telomeres. The replication protein machine that copies your DNA can’t grab on at the tip of the telomere. So, it doesn’t copy a few bits of telomere DNA between the tip and the spot where it latches on. That means each time a cell duplicates, the telomere gets a tiny bit shorter.

That ensures that the important DNA in the middle always gets copied. But those telomeres don’t last forever. When they get too short, senescence happens.

Scientists can stain DNA so they can see different parts under a microscope. Here the glowing white dots are telomeres. Weirdly, some animals like mice have longer telomeres but shorter lives. Dr. Zhu is studying mouse telomeres to figure out why that is. Image: NASA

Aging also has to do with itty bitty markers on your DNA called epigenetic modifications. They tell your body which sections of DNA to turn on or turn off.

Over time, those markers wear down. Maybe one marker starts out super pointy and then smooths out over time. It’s like how the soles of your sneaker wear down and lose their tread.

Scientists can look at those markers and tell how old the cell is, based on how worn down they are.

Here’s an epigenetic marker on some DNA. This marker is a methyl group. That means it’s one bit of carbon and three bits of hydrogen stuck together and attached to the DNA. Image: Ana Valente,Luís Vieira,Maria João Silva and Célia Ventura CC BY-SA 4.0, simplified by Dr. Universe

All those things—mistakes that happen during duplication, telomeres that shorten, and markers that wear out— seem to contribute to aging. Stress and problems in the environment might speed those things up.

But aging is important to us as a group.

“There’s an evolutionary reason we age,” Zhu said. “It leaves room for the next generation. That’s how we evolve.”

And population-wise, that’s something to cell-ebrate.

Sincerely,

Dr. Universe