Dear Lucy,

When I go to the veterinarian, they measure how big I am. They use a scale to check my weight. They find my length and height with a measuring tape.

But nobody can put a planet on a scale. Or wrap a measuring tape around it.

I asked my friend Katie Cooper about it. She’s a geologist at Washington State University. She studies our planet and other planets, too.

She told me we send satellites to orbit our solar system. When a satellite swoops around a planet, it snaps pics and takes measurements. Those images and measurements help scientists estimate the planet’s size and shape.

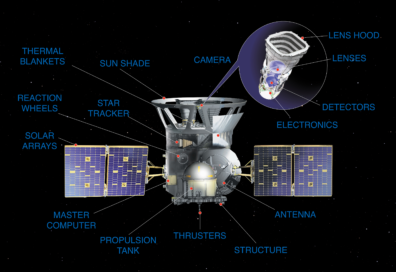

This satellite is a space telescope called TESS. It started sending data back to Earth in 2018. NASA

Scientists also measure how strongly the planet pulls on the satellite. That pull relates to the planet’s mass. They also calculate how much space the planet takes up.

Then scientists can figure out what the planet’s made of.

Scientists on Earth use seismometers to get a more detailed picture of what the inside of the Earth is made of. Those seismometers record vibrations from earthquakes. The vibrations change depending on the material they travel through. Then scientists can map inside the Earth.

Scientists have even set up seismometers on the Moon and Mars to “see” if they have similar interiors to Earth.

But what about exoplanets? They’re outside our solar system, orbiting stars trillions of miles away. It’s way too far to send satellites or put seismometers on them.

That’s why astronomers watch how exoplanets move through the sky every night. The motion is sometimes smooth. But sometimes it has a little wobble. The wobble depends on the planet’s mass and shape. It’s also affected by the gravity of nearby objects. Sometimes the planet pulls on its star’s orbit, too.

“When you throw a football, it may wobble,” Cooper said. “It wobbles based on the ball’s mass distribution as well as its shape and its size. It’s similar with planets.”

As an exoplanet orbits, it passes in front of its star. That blocks some light. So, it appears dimmer to astronomers on Earth at regular intervals. The dimming pattern is called a transit.

Astronomers track an exoplanet’s wobble and transit. They use math equations to calculate mass and size.

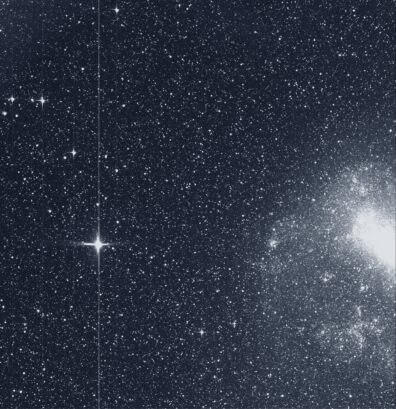

Some astronomers use public telescope data to find transits. Like the data from NASA’s space telescope named TESS. It records dimming patterns. Then astronomers comb through the data for clues about unknown exoplanets.

This image came back from TESS when it first when live in 2018. The bright star on the left is R Doradus. The bright area on the right is a nearby galaxy. Any astronomer can use TESS data, including professionals and people who watch the sky for fun. NASA

“Now we have computers that can search through these data systematically,” Cooper said. “That’s how we’ve gone from knowing about a handful of exoplanets to thousands.”

It’s not that different from how ancient people learned about planets in our solar system. They combined observation and math to estimate size and mass—long before satellites.

It turns out humans are amazing at finding patterns and asking out-of-this-world questions. Just like yours.

Sincerely,

Dr. Universe